By Michael Every, global strategist at Rabobank

- Developments in China continue to confound market optimists, with new talk of a “profound revolution” towards a new target of “Common Prosperity”

- Rather than simply react to these events, we analyze the history of Marxist-Leninist-Maoist Thought to try to put current moves under Xi Jinping Thought in a larger context

- This also provides a framework of a hypothetical Marxist policy path forwards

- We briefly discuss the meaning of Common Prosperity over time, and how it is a bellwether

- We conclude with likely market reactions to an economy not saying “because markets”

“Profound Revolution”?

Political developments in China have been front page news in the financial press over the past few months. Beijing’s crackdown on Ant Financial, largely dismissed by Wall Street, then spread to Didi and on to the broader sectors these championed, fin- and transport-tech; then it grew to encompass swathes of the economy, from tech to health to education to property to private equity to gaming.

In terms of tech, there are now sharp limits on IPOs in the US (mirrored from the US side) and new algo/pricing and data regulations that require Beijing to hold on to it; the private tuition field was made non-profit; there has been a sharp reduction in credit to property developers along with the official message that “houses are for living in, not speculation”, and rental increase caps of 5% annually; under-18s have been limited to just 3 hours of computer gaming a week, in allotted slots; and private equity has been cut off from residential investment.

Beijing has also called for curbs on “excessive” income, and for the wealthy and profitable firms “to give back more to society.” (Tencent already pledged $15bn.) This is also matched by: a social campaign against excessive business drinking, “unpatriotic” karaoke songs, and celebrity culture; ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ made obligatory at all schools and universities; and, as Bloomberg puts it, controls on social media financial commentary – “China to Cleanse Online Content that ‘Bad Mouths’ its Economy”.

This has all taken place under the slogan of “Common Prosperity”. (And for those who need the market-facing implications of this first, please see What is to be done?)

Going further, commentary reposted by Chinese state media on 30 August stressed these changes are a “profound revolution” sweeping the country, warning anyone who resisted would face punishment. It added: “This is a return from the capital group to the masses of the people, and this is a transformation from capital-centred to people-centred,” marking a return to the original intention of the Communist Party, and “Therefore, this is a political change, and the people are becoming the main body of this change again, and all those who block this people-centred change will be discarded.”

Notably, a WeChat blogger originally made the post, but it was then reposted by major state-run media outlets such as the People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, PLA Daily, CCTV, China Youth Daily, and China News Service.

The author also wrote that high housing prices and medical costs will become the next targets of the campaign –which was backed by an official announcement on 1 September– and that the government needed to “combat the chaos of big capital,” adding “The capital market will no longer become a paradise for capitalists to get rich overnight… and public opinion will no longer be in a position worshiping Western culture.”

Underlining a geopolitical element, the post also added that if China relied on “capitalists” to fight US imperialism it could suffer the same fate as the Soviet Union.

Fund pros’ revelation

Even ahead of the ‘revolution’ talk this had shocked markets – Chinese stocks have notably underperformed their US peers over 2021 despite an ostensibly better economic recovery (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

Indeed, Bloomberg published an op-ed asking: “Is Capitalism Just a Phase? China Struggles With the Math” and investors quoted as asking if Chinese stocks were “uninvestable”.

George Soros also ran an op-ed in the Financial Times titled “Investors in Xi’s China face a rude awakening”, concluding:

“Foreign investors who choose to invest in China find it remarkably difficult to recognise these risks. They have seen China confront many difficulties and always come through with flying colours. But Xi’s China is not the China they know. He is putting in place an updated version of Mao Zedong’s party. No investor has any experience of that China because there were no stock markets in Mao’s time. Hence the rude awakening that awaits them.”

However, thus far MSCI, which sets the benchmark for global portfolio allocation for EM equity investors, has not been moved to revise it China weightings. To them, this is all a technocratic policy adjustment and/or “periodic regulatory compliance measures”. The vast majority of Western market research also attempts to explain away what is happening in a similar fashion.

Yet China is an unashamedly a deeply political economy with an openly-proclaimed Marxist-Leninist-Maoist–Xi Jinping guiding ideology.

Reportedly, Western research analysts are now scrambling to read Xi’s past speeches to try to predict which sectors may be hit by a crackdown next. However, this still misses the larger key point: how can one correctly analyse likely future developments in a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist economy properly without having any knowledge of what Marx, Lenin, or Mao argued?

By contrast, this report will underline the thrust of these political/economic/philosophical thoughts, as the backdrop for Xi Jinping Thought and Common Prosperity.

This will allow us to:

1) Frame a Marxist hypothesis of what may be occurring;

2) Look at the shifting meaning of “Common Prosperity” over time as a bellwether, and what it means in this present context; and

3) Consider what the global market and geopolitical implications of such a strategy might be.

Note that this is by its very nature an ideological economic discussion, and that the necessity of doing so is very much in line with our late-2020 report that argued political-economy “-isms”, e.g., communism/capitalism, would soon be the key issue for markets to focus on, rather than the minutiae of fiscal and monetary policy shifts within a default neoliberal capitalism.

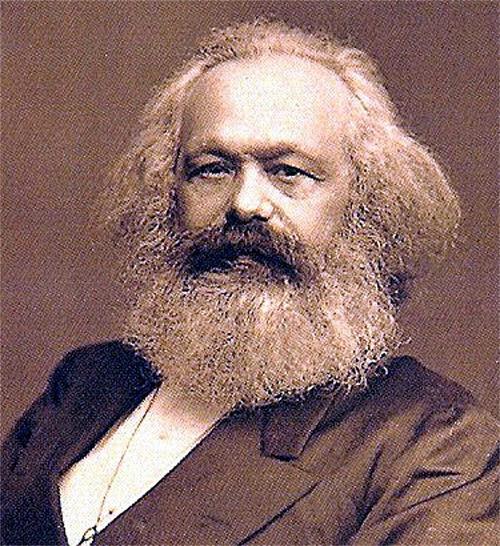

Marx

The collected works of Marx (with posthumous help from Engels) cover 50 volumes, and commentary on it thousands more. However, the relevant arguments today are simple to grasp.

‘The Communist Party Manifesto’ lays out a teleological, materialist conception of history: that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. In short, societal structures depend on the technology available and have always taken the form of an oppressed majority exploited by a minority.

We started with “primitive communism”; moved to agricultural and craftsman feudalism; and then to industrial capitalism. Under capitalism, the proletariat engage in class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the bourgeoisie, who only pay workers the bare minimum to survive, and keep the excess profits for themselves – The Labor Theory of Value (LTV). This class struggle will ultimately end in a revolution that restructures society again – to communism. Indeed, the Manifesto proclaims international revolution as its goal: “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!”

Ironically, most of the policy demands made by it hardly seem radical today: a progressive income tax; abolition of inheritances and private property; abolition of child labor; free public education; nationalization of the means of transport and communication; centralization of credit via a national bank; and expansion of publicly owned land. Indeed, much of early Marxism looks a lot like the de facto policy drift we already see in ‘New Normal’ economies today.

Notably, however, the Manifesto critiques socially-focused philosophies, noting: “A part of the bourgeoisie is desirous of redressing social grievances in order to secure the continued existence of bourgeois society. To this section belong economists, philanthropists, humanitarians, improvers of the condition of the working class, organisers of charity, members of societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, temperance fanatics, hole-and-corner reformers of every imaginable kind… The Socialistic bourgeois want all the advantages of modern social conditions without the struggles and dangers necessarily resulting therefrom. They desire the existing state of society, minus its revolutionary and disintegrating elements.”

In short, Western social-democracy –put forward as a technocratic explanation of Common Prosperity– is fundamentally antithetical to Marxism.

Marx went into far more detail in ‘Das Kapital’, which is still an important critique of modern economics today, in particular on the circulation of capital.

At root of neoclassical macro-econometric modelling is the assumption one starts with a commodity (C), exchanges it for money (M), and then buys another commodity (C): the chain of C>M>C means money is only needed as a lubricant, not as an end-goal itself, and overlooks banks’ and central-banks’ ability to create credit.

By contrast, Marx showed we actually start with Money (M), buy a commodity (C), add value via the ‘means of production’ (MP), creating a value-added commodity (C’) that is sold for M’, with M’-M being the gross profit. This is a realistic economic model that allows profit, money hoarding, (central) bank credit/capital, and *financial crises* to all be accounted for properly within capitalism in a way neoclassical economic and econometric models overlooking money/credit/banks cannot.

Moreover, Marx went into detail on the various forms of capital that exist, in particular: productive (i.e., making things – by exploiting labor); unproductive (i.e., the managers, accountants, and sales people also needed, etc., who are paid from the profit arising from the exploitation of the workers physically increasing the stock of goods); and fictitious – by which Marx meant financial assets unrelated to physical production, which he saw could become destabilizing, inflationary bubbles, and which were prone to market manipulation by large players, and crashes.

In short, to understand Marx is to understand the unstable dynamics of financial capitalism better than most capitalist economists even beyond the LTV.

One other crucial thing needs to be made clear about Marx and communism: he never described what it would look like. In his view, the state would “wither away” after the revolution happened. Communism was also not supposed to co-exist with capitalism, or compete with it: rather, it would supplant it via natural laws.

So, to very briefly summarise, Marx:

- Saw all profit as stemming from exploitation of labor;

- Foresaw dynamic global capitalism as doomed to fail;

- Dismissed social reformers as subverting revolution; and

- Explained the use of credit and the qualitative differences between productive and fictitious financial capital under capitalism.

This all has a key bearing on China’s “profound revolution”.

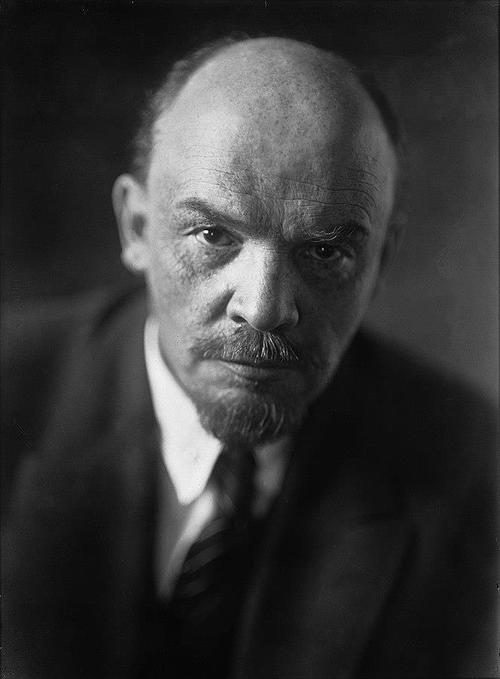

Lenin

Lenin, leader of the Russian revolution, made vital contributions to both Marxist theory and practice.

Crucially, Marx’s view of history meant that the communist revolution would occur in an industrialized economy: he had expected it to be Germany. Instead, it ended up happening in Russia, which was still only just emerging from feudalism.

An important debate at the time was therefore between the Bolsheviks (“the majority” in Russian), and Mensheviks, (“the minority” – though this did not reflect their actual popular support).

The Mensheviks believed they needed to develop Russia using capitalism first, in conjunction with more liberal forces and under parliamentary rules, and then have the revolution. Lenin disagreed, as had Marx, and it was his practical ruthlessness that saw the Bolsheviks seize power when it was “lying in the street”.

Politically, Lenin also added to Marxist thought to create Marxism-Leninism in three ways:

- A ‘vanguard party’ –the Communist Party– was necessary to raise the level of political consciousness and lead and guard the revolution

- The (ruthless) Dictatorship of the Proletariat was needed to run the state, the polar opposite of it withering away (but what happens when a revolution occurs and the bourgeoisie fight back); and

- Late-stage capitalism’s fusion of banks with industrial cartels, excess production, and need for new markets and profits, is a driver not only of revolution, but of geopolitical tensions and then war

Economically, Lenin introduced War Communism (1918-1921) to win the Russian Civil War, which involved: the nationalization of all industries; strict centralized management; state control of foreign trade; strict discipline for workers, with strikes forbidden; obligatory labour duty by non-working classes; the requisition of agricultural surplus in excess of an absolute minimum from peasants for centralized distribution; rationing of food and most commodities; private enterprise bans; and military-style control of the railways.

However, once the war was over, Lenin was forced to pivot to the New Economic Policy (NEP), under which there was a return to free market capitalism, subject to state controls, and state-owned enterprises operated on a profit basis -there were even “generous concessions to foreign capitalism.” In short, Lenin took the de facto Marxist/Menshevik position that he had to create “the missing material prerequisites” of modernisation and industrial development by falling back on a “centrally supervised market-influenced program of state capitalism”.

To summarize, Marxism-Leninism was politically ruthless but economically pragmatic in order to attain the physical means to achieve socialism/communism (used interchangeably by Lenin, as by Marx.)

Of course, the NEP came to an abrupt end in 1928 when Stalin assumed leadership of the USSR, at which point the traditional model of a Soviet economy, with agricultural collectivization, and a focus on heavy industry and 5-year plans, emerged.

Notably, Stalin also began to differentiate between socialism, which was painted by him as the imperfect state being built, as the transition stage towards the higher socio-economic goal of communism, which would eventually be achieved. He also shifted the USSR’s foreign policy goals away from Marxist-Leninist global revolution to ‘Socialism In One Country’.

That such swings in policy direction are possible under a Marxist-Leninist system is itself already a key lesson to be drawn for the present day.

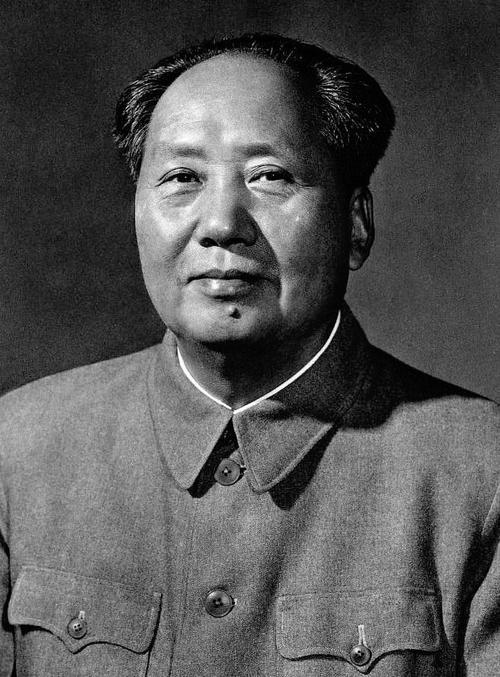

Mao

Maoism, or Mao Zedong Thought, added to Marxism-Leninism in several ways:

- It stressed Leninist realpolitik view of the role of a revolutionary party, e.g., with the key quote that “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”;

- The peasantry are the revolutionary vanguard in pre-industrial societies –such as 1940’s China– rather than the industrial proletariat. Mao therefore differed from Marx on the theory of the inevitable cyclicality in the economic system.

- Rather than waiting for industrial development, Mao’s goal was to unify the Chinese nation in order to realize the communist revolution;

- Accordingly, Mao’s theory of the ‘mass line’ holds that the Chinese Communist Party must not be separate from the popular masses, like an elite vanguard, either in policy or in revolutionary struggle;

- Mao’s theory of Cultural Revolution states that the proletarian revolution and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat does not wipe out bourgeois ideology. The class-struggle still continues and even intensifies during socialism, therefore a constant struggle against bourgeois ideologies and their social roots must be conducted;

- Mao argued contradictions are natural and the most important feature of society. Since society is dominated by a wide range of contradictions, this therefore calls for a wide range of varying strategies, e.g., a revolution, to fully resolve antagonistic contradictions between labour and capital; and ideological correction to resolve contradictions arising within the revolutionary movement to prevent them from becoming antagonistic.

- Mao also oversaw a Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s following the USSR’s break from Stalinism.

Economically, Maoism co-opted so-called pro-CCP “Red Capitalists” such as Rong Yiren before embracing Stalinist collectivism and industrial development via 5-year plans – which ended in severe economic damage during the Great Leap Forward. Economic development was further set back by the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.

In summary, Maoism represents an extension of Marxism-Leninism to Chinese socio-economic conditions, focused on the link between the Party and the population, as well as resolving bourgeois tendencies and/or ideological contradictions. However, there was no room for Menshevik/NEP-style economic pragmatism.

Post-Mao

The starting point for most Western analysts looking at the Chinese political economy is Deng, who emerged as leader of the CCP following Mao’s death in 1976. Mao welcomed US President Nixon to China, but it was Deng who opened China up economically with the proverb that “it doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, if it catches mice it is a good cat.” This was a stepping stone to the official adoption of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”, a Leninist NEP-style program, where the “primary stage of socialism” required markets and private capital – while still stipulating that China needed growth before it pursued a more egalitarian form of socialism, which in turn would lead to a communist society.

In 2000, when China joined the WTO, Jiang introduced “The Three Represents” to modernize the CCP’s links to a vastly-changed society. Rather than just the proletariat, the Party was now seen as representing: the development trend of China’s advanced productive forces; the orientation of China’s advanced culture; and the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people, which covered far more political bases – including business. In 2003, Hu added “The Scientific Outlook on Development”, pledging scientific socialism, sustainable development, social welfare, a humanistic society, increased democracy, and, ultimately, the creation of a Socialist Harmonious Society, taken by many as further liberalization.

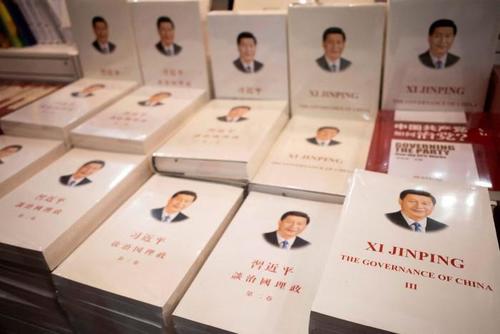

Xi

So to the present day.

The now-shocked op-ed writers at Bloomberg and the Financial Times and the stunned Wall Street analysts all clearly regarded the 2000’s era, rapidly-growing, reforming, globalizing China as being either the final stage of its political-economic development or a staging post towards even further liberalization. However, this overlooked the fact that Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, or more commonly ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ (XJT), has been a growing body of work since 2017.

At the 19th National Congress of the CCP, XJT was incorporated into the Party’s Constitution, and at the First Session of the 13th National People’s Congress in 2018, the preamble of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China was also amended to mention XJT, underlining its political significance given it joins only Mao and Deng Thought on that list of fundamental national doctrines.

So, crucially, what does this body of work add to Marxist-Leninist-Maoist Thought?

There is a simple 14-point basic policy list to follow:

- Ensuring CCP leadership over all forms of work in China;

- The CCP should take a people-centric approach for the public interest;

- The continuation of comprehensive deepening of reforms;

- Adopting new science-based ideas for innovative, coordinated, green, open and shared development;

- Following socialism with Chinese characteristics with people as the masters of the country;

- Governing China with Rule of Law;

- Practice socialist core values, including Marxism, communism and socialism with Chinese characteristics;

- Improving people’s livelihood and well-being is the primary goal of development;

- Coexist well with nature with energy conservation and environmental protection policies and contribute to global ecological safety;

- Strengthen the National security of China;

- The CCP should have absolute leadership over China’s People’s Liberation Army;

- Promoting the one country, two systems framework for Hong Kong and Macau with a future of complete national reunification and to follow the One-China policy and 1992 Consensus for Taiwan;

- Establish a common destiny between Chinese people and other people around the world with a peaceful international environment; and

- Improve party discipline in the CCP

The above combines technocratic goals that would be well-received in all economies, as well as specific honorifics to maintain CCP ideological continuity. As such, it is easy to see how a Western analyst with no interest in political economy or Marxism could, in 2019, see “reforms”, “people-centric”, “rule of law”, “improve livelihoods and well-being”, “energy conservation”, “environmental protection”, “global ecological safety”, and “peaceful international environment”, and feel entirely at ease.

Yet a key 2013 speech and 2014 ‘The Governance of China’ book series together provide the intellectual spine of XJT – and they focus on China’s place in history, strategic competition with capitalist nations, and a plea to adhere to the goals of communism.

In particular, it was “Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought that guided the Chinese people out of the darkness of that long night and established a New China.” – not Deng or the post-2000 economic reformers. Looking ahead, “the consolidation and development of the socialist system will require its own long period of history… it will require the tireless struggle of generations, up to ten generations.

Fundamentally, “Marx and Engels’ analysis of the basic contradictions in capitalist society is not outdated, nor is the historical materialist view that capitalism is bound to die out and socialism is bound to win… The fundamental reason why some of our comrades have weak ideals and faltering beliefs is that their views lack a firm grounding in historical materialism.”

Furthermore, as alluded to in the 30 August commentary quoted at the beginning, a very particular focus on the collapse of the USSR: “Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party fall from power? An important reason was that the struggle in the field of ideology was extremely intense, completely negating the history of the Soviet Union, negating the history of the Soviet Communist Party, negating Lenin, negating Stalin, creating historical nihilism and confused thinking. Party organs at all levels had lost their functions, the military was no longer under Party leadership. In the end, the Soviet Communist Party, a great party, was scattered, the Soviet Union, a great socialist country, disintegrated. This is a cautionary tale!”

As noted, XJT is now the official curriculum at schools and universities across China – meaning that an understanding of its core messages and targets is of the utmost importance to markets.

Presumably, at some point ahead Common Prosperity will be wrapped into XJT in a more formal manner too.

Marx to Market

Before looking at Common Prosperity specifically, it is time to “Marx to market”: that is to look at everything we have just shown the reader, and to try to draw out what this implies is now happening in China from a hypothetical Marxist perspective, i.e., the one the markets so clearly lack.

The 14-point list of course shows which sectors are going to be favored going forward: green, the environment, science, and national security. However, the same list would arguably apply to almost any global economy today, from President Biden’s America to Boris Johnson’s Britain, which makes it far less useful. The 14-point list does not tell us anything about which sectors will not be favored by Beijing, or which will see harsh regulatory crackdowns, or what the overall operating environment for businesses and asset-managers in China will be like.

Here we must stress that XJT openly draws from Marx, Lenin, and Mao. Using them as a guide, a hypothetical framework can be drawn in some respects.

XJT holds to Marx’s historical materialism, which predicts capitalism will collapse due to its own internal contradictions, even if it also believes this is not imminent. However, even given the deep-rooted structural problems in most Western economies, it seems unlikely this view is purely based on the debunked Labor Theory of Value. Far more likely, is a Kaleckian critique of the LTV –i.e., falling labor share of GDP– with the circulation of capital –i.e., an addiction to debt– and of productive, unproductive, and fictitious uses of capital – i.e., as the West continues to lean on asset bubbles and QE rather than productive capital investment. Moreover, neoliberal capitalism has seen increasing economic concentration, as Marx predicted. Even much of the West sees this critique as valid, and worries about the future outlook.

Of course, we could see a burst of OECD ‘Build Back Better’ that reshapes economies and supply chains – but Leninist theory suggests this leads to growing geopolitical tensions and the risk of war. Xi Jinping has openly warned the PLA of the need to be ready for war on several occasions in recent years, as one would from a Leninist perspective.

For China, this therefore suggests that rather than embracing a destabilizing neoliberal, monopolistic, unproductive financial capitalism, with all of its resultant socio-economic problems, just to build capital stock, it needs to pivot back towards more state-direction within a Leninist-NEP mixed economy – and with a far larger national-security focus at the same time, just in case.

If that means making for-profit education non-profit to make education cheaper, so be it. If it means to “prevent the irrational expansion of capital” and “barbarous growth” of private monopolies, as Xi Jinping declared on 31 August, then that is a problem for those sectors.

If that involves telling under-18s they cannot play computer games for more than 3 hours a week, so be it. Children addicted to computer games are not goals of a communist society, or any healthy society.

If that involves rental caps, then that is what will have to happen too.

In short, more productive capital, please; less unproductive or fictitious capital, thank you very much. Far more productive consumption (i.e., made in China goods), please; far less unproductive (i.e., “Western” services like gaming), thank you very much.

This does not mean that market forces are about to be wiped out. Marx argued for their dynamism, and XJT embraces a “socialist market economic system”. However, these need to be corralled into the right areas – which does imply a higher degree of central planning. At the same time, it means accepting the ‘right’ level of return – that ensures a harmonious outcome for Chinese society as a whole, not just that of a portfolio.

Indeed, as XJT draws from Marx and Lenin, it also draws from Mao. Recent developments point to a thrust to get the CCP back in touch with the masses, not just the several hundred million who have benefited so handsomely from the NEP economy of the past few decades. Moreover, XJT talks about wavering ideological faith in the party, which smacks of the need to overcome contradictions with ideological correction. The same argument –and the 30 August “profound revolution” commentary– suggests the need to deal with ‘bourgeois elements’ in the economy who may reject the necessary medicine.

So the above is a hypothetical Marxist perspective on what is happening. It may come as a shock to Western investors who assumed China was capitalist, and try to ascribe purely technocratic intentions to every development everywhere.

However, if they had read Marxist theory or history they would have recognized that ‘NEPs’ are used to help move the economy up the development ladder towards a higher stage of socialism and then to communism; and meanwhile neoliberal capitalism is growing unwieldy, unwelcome, and unpopular even within the West itself, as we see from constant talk of the need to Build Back Better – which China seems willing to act on.

The Zhejiang example

But do we have any actual evidence from the ground to support this Marxist theory? Perhaps, yes. Bloomberg recently carried an article looking at the province of Zhejiang (population 65m, and home to Alibaba), which has an existing pilot experiment with Common Prosperity.

Crucially, what is being seen there is not a tax-and-spend or a welfare state shift, which are again Western, market conceptions of how political-economy should work; nor is it seeing a return to state ownership of the means of production, i.e., nationalization, which is the final stage of communism. Rather we see a strategy to force capital to flow to areas previously starved of it, alongside huge efforts to bring down living costs – which is entirely in line with the Marxist theory just put forward. Specifically, we see:

- Direct targeting of inequality (of intra-provincial GDP per capita gaps between rural and urban areas);

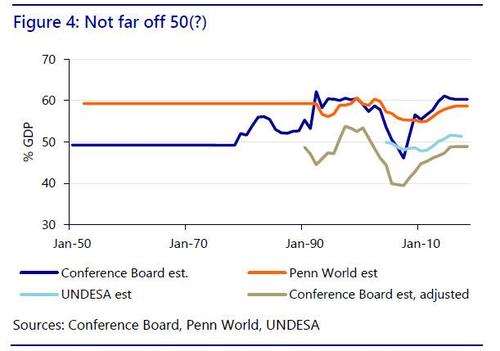

- Aiming to increase the labor share of GDP to > 50%;

- More urbanization;

- Property taxes (on private housing) and building new state-owned rental properties (i.e., social housing);

- Letting people without official hukou residence access state services, which is a genuine revolution;

- More spending on social services – and “donations” from local billionaires collectively worth $236bn;

- Lower cost business loans for favored sectors, including manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism;

- SOEs building more infrastructure, “even if it generates low returns”; and

- Breaking up monopolies.

As such, we get a ‘Build Back Better’ picture of a “socialist market economic system with Chinese characteristics”: potentially higher growth, but lower returns; less luxury and more mass-market; and far more state regulation. This is something neoliberal markets currently don’t understand and presumably won’t like: they clearly prefer lower growth and higher returns; less mass-market and more “premiumisation”; and far less regulation.

However, significant obstacles still need to be tackled. Most obviously, even using markets to enforce centrally-planned goals still assumes that such central planning can guide them towards generating the productivity gains that will be needed – an issue non-NEP Marxist economies struggled with in the past in the absence of markets.

Importantly, the CCP has announced it will hold a key plenum in November – what policy changes this portends against the current backdrop remains to be seen.

Capital problem to labor with

Another obstacle to increasing the labor share of GDP to over 50% to boost consumption must also be stressed.

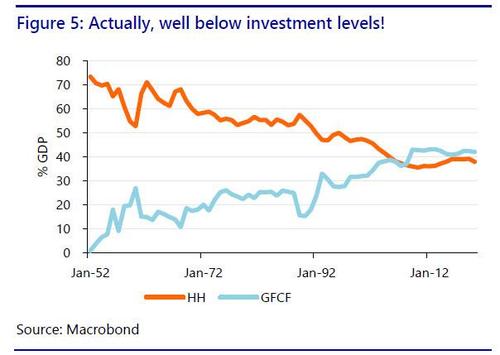

According to most data, China’s labour share of GDP is already over 50% (Figure 4), but this this does not capture China’s very low share of household (HH) spending in GDP, which is even lower than the share to gross fixed capital formation (GFCF, Figure 5).

Does Common Prosperity mean lower investment and higher consumption? That runs counter to the imperative for more “productive” capital and for more lending (at low rates) to new SMEs and sectors. It would also suggest an employment shift towards more “unproductive” sectors.

Yet if household spending rises and investment spending stays the same, or rises, then national savings will fall, and China will run an external deficit (and debt will rise further). The PBOC recently stressed this was a sign of economic weakness, and it would open the door to major market volatility over time – something that is clearly not desired.

How can these inherent contradictions be resolved? Logically, only with an unrealistically-high net export surplus, creating major trade/geopolitical problems.

What is to be done?

What we need to do now is summarize the major underlying arguments made so far:

- First, while many in the West/markets approach China as having a de facto neoliberal capitalist system, this view is not just overly simplistic, it is arguably wrong. While many of the things China says may sound “Western” or easily-recognizable, e.g., “green”, “sustainable”, “people-centred”, etc., this does not mean that the underlying political economy is Western.

- Second, while the West considers economic thinkers of the past to be exactly that…of the past…China is not just paying lip-service to Marxism: it is taking cues from the roots of Marxist thought traditions, while adding modern-day interpretations in order to choose its own path. With the Western capitalist system clearly in trouble, China’s leadership feels emboldened to push ahead in this regard.

- Third, whereas in the West change is gradual, or non-existent, and usually part of a democratic model in which consensus is required, in China far more dramatic changes can happen suddenly if needed for the perceived greater good. Such changes are happening, and are currently speeding up, not slowing down.

- Fourth, while we can perhaps see the ideal destination to Common Prosperity, the journey itself is likely to be extremely bumpy, and involve many more major zero-sum trade-offs. However, the political imperative appears to be there to continue to move down this path.

So, given this backdrop, what does it mean for the economy? What does it mean for markets? What does it mean for geopolitics?

In terms of the economy:

1. The current policy shift may add to pre-existing downward pressures on Chinese growth by reducing business confidence and scaring off foreign investors, while also failing to square the circle between the needs for a trade surplus, higher household spending, and sustained high investment.

2. …or it may lead to sustained high growth of a more balanced kind, e.g., more social housing and less private housing; more high-tech/green manufacturing jobs, and fewer gig economy/services jobs.

3. Western exporters to China focused on the higher-income/luxury sectors may be unhappy in either case.

In terms of markets:

4. Chinese equities may continue to struggle to keep up with those of the US, particular in sectors the government focuses its sights on. Risks to the housing sector also loom large if comments about too-high prices are followed up on.

5. It is an ironic positive for global bonds, and most so government bonds in China – although as a one-way street for those who get in early to the latter, and with realization that they are there for the duration of the political and FX ride, wherever it eventually leads.

6. On balance, it is more likely to be a long-run negative for CNY than a positive. In the short-run, however, the rhetoric on capital markets suggests no appetite in Beijing for FX volatility. If we were to see a universal move in USD higher ahead, e.g. by Fed tapering, then CNY will move lower – while staying largely unchanged against every currency except the Dollar, no doubt; and

7. While the Fed and ECB have not made any mention of developments in China so far, this is going to matter to the US and EU economies too. It may mean even more “fictitious capital” (QE) for them, just as China tries to focus on the “productive” side even more.

In terms of geopolitics:

8. Geopolitical and trade tensions, which flow back to the economy and markets, are only going to worsen.

9. For the West, this poses a major challenge. The risks for investors in China are clear, and to Western net exporters if China sees slower growth, or more domestically-focused and sourced growth. However, a whole different set of political-economy problems would be created if China’s new state intervention policies work well – on what basis would a struggling West be able to then reject them at the ballot box?

So, “Pro-Fund” or “Profound”?

To conclude, this report represents an opinion that deliberately steers away from a traditional ‘Street’ view to try to present an alternative way of seeing things. There are of course many other views: yet the one here would have prevented a lot of concern and surprise among Western investors in China this year, and may yet prove a guide for what comes next.

Is the ultimate future of China pro-fund or profound revolution? It depends – and perhaps ultimately on if one sees there are observable laws to the progress of history or not!

PLEASE TELL YOUR FRIENDS ABOUT CITIZENS JOURNAL Keep us publishing – Please DONATE